Nothing more worries individual

investors than not knowing what to look for, and choosing the wrong

companies to buy. How do I know when a stock is

cheap? How do I tell if it will go up over time?

But that doesn't work for me. I'm much more interested in what a stock will do tomorrow than in what it did yesterday-- and I don't believe I can learn much about tomorrow based on yesterday. Which means I have to find other ways to value the companies I buy. I need to look at non-financial criteria. I've written about this before. But because it gets so much investor attention and because it seems so difficult to people starting out, I'm going to revisit it here.

But that doesn't work for me. I'm much more interested in what a stock will do tomorrow than in what it did yesterday-- and I don't believe I can learn much about tomorrow based on yesterday. Which means I have to find other ways to value the companies I buy. I need to look at non-financial criteria. I've written about this before. But because it gets so much investor attention and because it seems so difficult to people starting out, I'm going to revisit it here.

Most money managers try to steer an investment portfolio by looking in the rear-view mirror

1. First up, I want a great brand, and often a change agent. By

that I mean I want a company people have heard of, and one which is dominant

in an industry. Examples include Netflix and Apple. Sure, some people

gotta hate because these companies steamroll the competition (respectively:

cable TV/Blockbuster/neighborhood video rentals, and Microsoft-Dell-Gateway-Sony-Nokia-Blackberry ...)

but that's what makes them such compelling investments. These companies are so

strong they redefine the way business is done in their category. It is no

longer possible to have a realistic discussion about the state of retail without

mentioning Amazon, or about television without Netflix. They change

everything and as consumers we can either get on board or get left

behind.

2. Second, I like to see a wide moat. Simply put, this is the distance between the

business in question and the nearest competitor, which usually indicates the

difficulty of the competitor catching up in the next few years. A good example

is Starbucks. On the surface Starbucks sells a commodity-- coffee. But what

makes them so valuable is they do it with panache: across a massive swath of

the globe, at tremendous profit (remember when we thought $3 for a cup of

coffee was crazy?) and they do it in their

ubiquitous neighborhoody, comfortable, jazz-infused stores. Sure

another business can mimic what they do-- and thousands have-- but Starbucks

has such a massive head start and with worldwide brand recognition and a

well-established level of quality product and service that no one can

realistically catch them for years to come.

Another great example of a wide moat is

Visa. Almost regardless of where you travel, time of day, language

spoken, or currency used, they take Visa. Even MasterCard can't catch up. And

newer methods of payment-- ApplePay, PayPal-- are just alternative ways for

most people of using their Visa card (both systems tie into an existing card

account), and in any case are many years away from the level of saturation Visa

has worldwide.

|

| Amazon's AWS data center |

3. Next, I'm looking for a business which is in strong growth mode. This one is obvious: a company whose sales are expanding rapidly year over year as they add new stores, or put out new products or services, or buy up their competitors (or kill them). It is nearly impossible to value these businesses financially based upon their past performance because in a lot of cases they're growing too fast for last year's numbers to mean much. For example, a division of Amazon called Amazon Web Services, or AWS, offers cloud computing services to other businesses (Netflix among them). AWS is only a few years old but it's currently growing at something like 80% per year. In time it could be worth more than the company's "traditional" ecommerce business. A number of other, more established technology companies have even abandoned the cloud services industry in the face of Amazon's juggernaut (Hewlett-Packard did that just that last week). Partially as a result, Amazon's stock valuation has increased over 100% in 2015 alone. That's a ride I want to be on.

4. After that, I want a business

with low debt. Typically, manufacturers have higher

fixed costs for heavy equipment and materials, so they must borrow more for

those items and maintain higher debt levels on their corporate books. By

contrast, software companies and online services generally have much less need

for serious capital (their highest costs are often their people) so they tend

to carry less debt. Generally speaking, a company with

relatively little debt has a lower bar to clear to make a profit, and therefore

has a much wider operating margin to work with. As a side benefit, businesses

carrying little debt can usually better weather difficult economic climates or

other sales downturns.

Long Term Debt is a line item on any

public company's Balance Sheet. This can easily be found on Yahoo! Finance by

entering the company's name in the Quote Lookup field.

Ideally (but not exclusively), Long Term Debt should total 25% or less of

the company's annual revenues, which is available in the same location on

Yahoo!, but on the company's Income Statement.

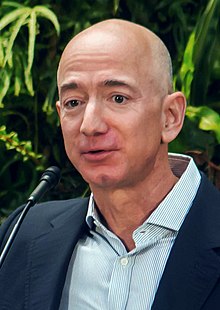

|

| Amazon Founder/CEO Jeff Bezos |

5. The next has to do with the company's

executive leadership. I want smart, transparent, confident

leaders who are less interested in Wall Street analysts'

quarterly expectations and more interested in long-term growth, product quality

and customer service. You can read interviews, listen to conference calls with

press, watch them on YouTube: are

the executives of your business providing clear direct answers to questions

posed? Are they worried about share prices or customer satisfaction? What do

they say about competitors, about new technology, about growth plans? Do they

come across as a little phony, a little slimy or more genuine and trustworthy?

Do you believe them? Like them?

Financial research and the news are added to

my existing customer experience, and together they serve to enrich and deepen

my knowledge

The most famous example of straight-talking, trustworthy leadership

is Berkshire Hathaway's billionaire leader Warren Buffett. In his annual letters to

shareholders, Mr. Buffett comes across as down-to-earth, honest, folksy and

even funny. Whatever the business he's describing he tells is like it is,

explaining how it works and why it's important as he goes along. Reading his

letters is some of the best business education you can find, not to mention a

model for others and entertaining to boot.

6. Finally, I prefer businesses with

which I have first hand customer experience.

I've found it invaluable: how better to judge a business's performance

than by being a consumer of their products and services over time?

This one is a slightly higher hurdle

because most of do business with only a handful of public

companies relative to the thousands worldwide in which we

could invest. But in truth there is no shortage of investment

opportunities just among those: manufacturers of toothpaste and paper

towels, clothing and shoes, electronics and furniture, housing and automobiles,

sporting goods and appliances. Makers of entertainment products like books,

magazines, music, movies, television, video games. Service companies like

utilities and cellular, cable and internet, shopping clubs and online

retailers, banks and even brokerages.

For example, I prefer Under Armour's

athletic clothing to Nike's both for fit and durability, and have since I

stumbled onto it about 10 years ago. I'm a huge fan of Amazon's Prime service,

which is preferable for me rather than shopping around for vacuum filters

that fit, or having the right gas grill shipped to my door. Despite living

in Seattle my coffee snobbery has never advanced past Starbucks' fresh roasted

espresso beans. I generally enjoy Disney's

Marvel superhero movies. I've mentioned Netflix and Visa. Also there's LinkedIn

and Twitter, IMAX and Zillow, all of which have come up with a great new

business concept or revolutionized an everyday process like career networking

or house shopping or movie-going.

By being a customer/user (even an

unpaying one), I better understand the value proposition these businesses offer

and I've already got a finger on their pulse. I notice when quality slides or

new services are added, and this information informs my investment decisions.

Financial research and the news I read are additional to my existing, ongoing

customer experience. Together they work to enrich and deepen my

knowledge.

This list of criteria has provided me

close to 80% of what I need to know prior to investment-- but you likely will

not find all 6 in one company very often. It happens, but those are rare. Look

to get several in one stock. I've listed several of them here, but there are

probably a couple of hundred if you look hard enough. This method is largely

unscientific and non-financial, and therefore is an unconventional way of

assessing a stock-- but then being somewhat contrarian is my nature. Some pro

stock-pickers and market timers might poke fun at you; they certainly have at

me. Generally speaking, however, my returns crush theirs... though I don't

think they believe my numbers. A high-class problem if there ever was

one.

Drifting to Fifty | Random unrelated nugget of the week

If you reset your car's side mirrors from reflecting your own rear fenders to reflecting that empty zone between the edge of your peripheral vision and the edge of what you can see in the rear-view mirror, then you will eliminate blind spots.

If you reset your car's side mirrors from reflecting your own rear fenders to reflecting that empty zone between the edge of your peripheral vision and the edge of what you can see in the rear-view mirror, then you will eliminate blind spots.